The Mindful Mona Lisa: Transforming Nature and Time's Leviathan

In a sense, this blog – now in its fourth year – was prompted by a poem Leonardo wrote about a whale.

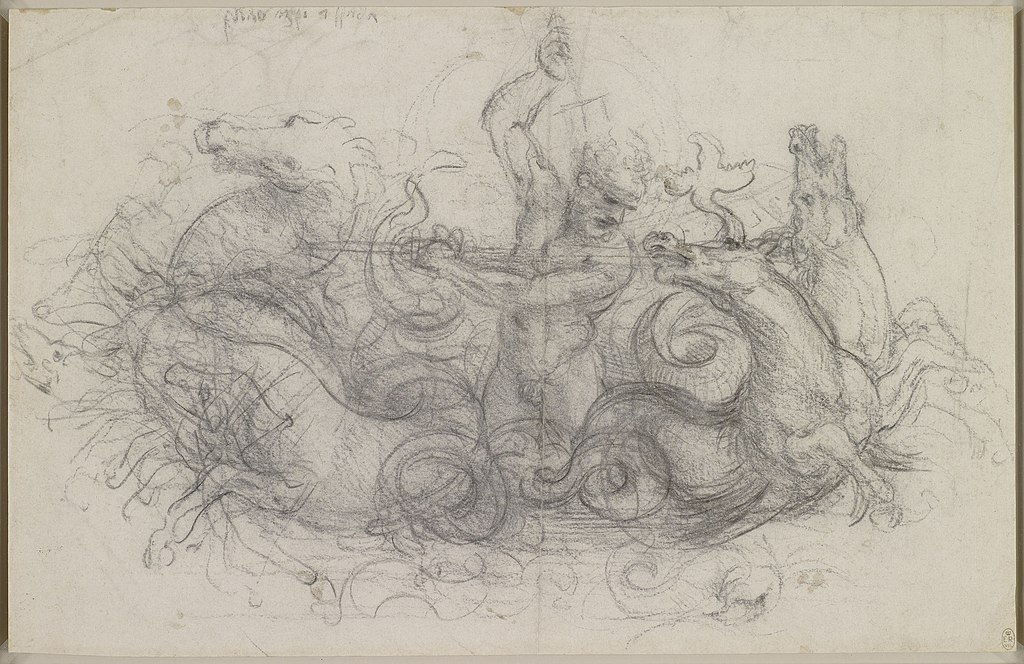

After encountering a giant sea-skeleton in an exposed layer of the geologic fossil record, the earliest discoverer of plate tectonics (or close) wrote “Time, destroyer of all created things” – echoing with premonitions of Oppenheimer’s Bhagavad Gita quote – “look how this great sea creature’s bones have now been changed to rock, holding up the whole mountain above them.”

Leonardo then went a step further, composing a short prose poem in three revisions to articulate this image yet more fully, “o quande volte tu veduto.” It was Calvino’s discussion in Six Memos of this poem by Leonardo, as an example of “Exactitude” in the artist-scientist’s fusion of verbal and visual imagination, that led me to consider Leonardo capable of designing an allegory of Esperienza in La Joconde.

Paradoxically, time destroys all things except for one: experience, which it increases and preserves.

Calvino’s sixth and final Memo, titled “Consistency” but as yet unwritten at the time of his passing in 1985, was to have discussed among other topics Melville’s “Bartleby the Scrivener.” Perhaps for this reason I decided to re-read Moby Dick this summer in search of possible Dante references, or parallels to Emerson’s “Experience,” or some connection back to Bartleby and consistency.

In our day of terrifyingly rapid change to both climate and all natural ecosystems, characterized by almost unfathomable loss and destruction, it is traumatic to read in romanticized detail of the hunting of whales. This likely read differently in 1851, a time when most people worked in the confining toil of either farms or factories yet were drawn by fascination to the sea as an open and inexhaustible alien frontier. In 2023 however the tone reads wrong somehow (unlike Bartleby, which Six Memos ranked above Moby Dick), and both Ahab and Ishmael seem too threadbare of conscience to regard unskeptically. The best part in some ways is the set of quotations about whales that begins the book, confirming the species’ symbolism of both time and nature’s great scale; the references to weaving as whales are sighted by the Pequod also resonate.

Melville does not, however, like his contemporary Emerson, discuss the concept of experience per se as an aesthetic or philosophical category as I argue Leonardo has done. Rather his sea-epic seems to reject the abstract or contemplative in a cruel yet fateful embrace with the real, the physical and inevitable. One may see in this repudiation perhaps a mirror of Henry James’ criticism of Walter Pater as too refined, speculative, and Aestheticist, favoring “an ideal woman over the real one,” intellect over life and imagination over the action without which it is never fully real. One sees in James and Melville elements of an identifiably American physical optimism – a grim yet stoic heroism toward suffering and material obstacles – which has become more difficult to sustain.

We may question James’ judgment of Pater perhaps, or temper it, by reading the latter’s Marius the Epicurean which he wrote in reply to much the same criticism of self-absorption leveled at his 1873 essays The Renaissance. In Marius Pater sought not to press forward but rather look backward to the time of Marcus Aurelius to consider how the near proximity of ancient pagan ritual, Stoicism, the new shoots of monotheism, and the Epicurean ideals of De Rerum Natura might align order, justice, humanity, time, science, imaginative experience, and nature to redeem the promise of sustainability beyond mere triumph over the materially difficult. This nuance remains fundamental for us today.

As the work of Anil Seth has begun to demonstrate, it is the imagined states of “predictive regulation” and “interoceptive inference” which allow the physical engagement of consciousness with its outer material environment to occur, whether in aesthetics, sense perception, embodied wisdom, or enactive cognition; and all these rely first and foremost on Pater’s almost-sacred principle, gathered in part from Leonardo and Dante, of subjective experience combined with experiment into the core, engine, and synaptic center of a fabric which includes all things.

Next blog: Alchemical metaphor in Browne, Chaucer, Jung, Newton, and Tokarczuk