The Mindful Mona Lisa: Bridges of Peace and Understanding

Francis Bacon’s Novum Organum (1620) is one of the most influential scientific texts of the early modern era. Interestingly, in the context of this blog’s novel hypothesis that the Mona Lisa may be an allegory of “Esperienza” -- Italian for both experience and experiment -- Bacon’s tract uses the word “experience” over thirty times, including examples like this:

- “The foundations of experience (our sole resource) have hitherto failed completely or have been very weak; nor has a store and collection of particular facts, capable of informing the mind or in any way satisfactory, been either sought after or amassed.”

- “(O)ur only hope is in the regeneration of the sciences, by regularly raising them on the foundation of experience and building them anew, which I think none can venture to affirm to have been already done or even thought of.”

This key concept of “experience” animated a conceptual exchange interconnecting the arts and sciences at the birth of modernity, spanning from the Mediterranean to across the English channel, uniting a new diversity of scientists, painters, poets, and philosophers throughout Europe and Asia in a shared thematic space. Even Cervantes’ Don Quixote of 1604 weighed in, with ironic gravity: “there is no proverb that is not true, all being maxims drawn from experience itself, the mother of all the sciences.”

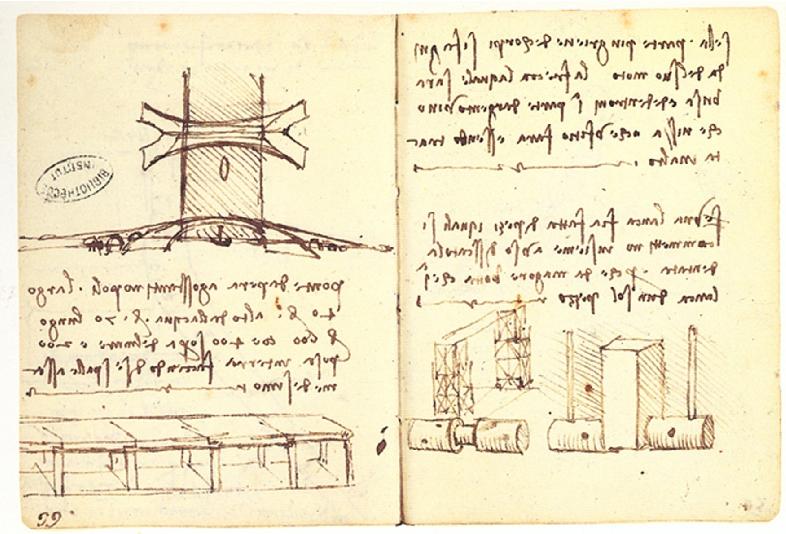

Historian of science Pamela Smith writes in marvelous detail about “experience” in this sense, noting the “artisanal epistemology” that brought productive techniques and knowledge of materials from early modern professions like metallurgy, alchemy (“chymistry”), textile manufacture, and oil painting into written and philosophical discourse including scientific method.

In Wolfgang Leidhold’s 2023 book The History of Experience, he recalls a vivid childhood memory: “I remember how I suddenly experienced myself as part of a big whole: Down in the kitchen sat the stargazer, up there high in the sky stood the stars, and both sides were linked by my perception and the binoculars…. it is clear that the structure of experience is three-part: two sides linked by some kind of a bridge.”

These dynamics inform more than just art and science; they also shape modernity’s understanding of both philosophy and politics. John Dewey once described democracy as “conjoint communicated experience.” Hamilton’s Federalist No. 85, published in 1788, quotes Hume on the fundamental role of experience (using ALL CAPS!) in how political systems evolve through time. William Blake (also in 1788, but across the Atlantic) wrote “the true faculty of knowing must be the faculty which experiences,” and may have dreamt of a bridging dialogue between diverse traditions (much as Leonardo’s bridge design for Bayezid II might have spanned the Bosphorus in 1500). Jung used a similar metaphor to describe the history of ideas as a “bridge of the spirit.”

Art and science play an indispensable role in cultivating the richness of each person’s unique experience, personality, and identity. They also embody the fabric of communication and interconnection which constitute the lived reality of any complex and vibrant society. This “conjoint” network structure of meaning, having roots both wide and deep, makes democratic governance based on rights, mutual well-being, and the rule of law possible.

As the novelist Olga Tokarczuk, trained as Jungian psychologist, asserts in her Nobel speech of 2018: “…the tales of our experience that literature creates have their own dimension. That is why I believe I must tell stories as if the world were a living, single entity, constantly forming before our eyes, and as if we were a small and at the same time powerful part of it.”

Next blog: Machiavelli, Marlowe, and Faustian Experience