Leonardo Volume 57, Issue 2 Criptech & the Art of Access

Introduction

Vanessa Chang and Lindsey D. Felt: Criptech and the Art of Access

This special issue of Leonardo, “Criptech and the Art of Access” convenes practitioners of the emergent movement of criptech art. Criptech art names “a collective group of disabled artists who engage with digital and scientific technologies as both a creative medium and avenue for crip practice.” As issue editors Lindsey D. Felt and Vanessa Chang write, “in this context, crip is both a noun and a verb; it is a subject position with political agency, and it is also an action that effects change through the interrelation of entities. When disabled people crip objects and environments to make access, they also reinforce disability’s place in the cultural landscape.” By bringing this “inventive, noncompliant approach” to the field of media art, these artists forge new approaches to creative technologies even as they affirm a politics and aesthetics of access.

This gallery gathers some of the artworks and cultural artifacts that animate many of the essays in the issue. From ecological social practice to XR, they showcase the extraordinary range of criptech art. Explore this archive to experience these creative practices and read more in the issue.

Articles

Laura Forlano and Itziar Barrio: From Data Doubles to Data Demons

This article describes a collaboration between the authors around a series of robotic sculptures that were created by Barrio with data from Forlano’s “smart” insulin pump and sensor system. Forlano, a type 1 diabetic for over 10 years, expands upon previous writing about her experience as a “disabled cyborg.” As CripTech art, the robotic sculptures, discussed here as data demons, complicate and expand contemporary discourses on artificial intelligence and design. By engaging themes such as data as labor, data as material, and data as relations, this article ultimately argues that both people and technologies are disabled.

Itziar Barrio, 2023, Concrete, spandex, lighting filters, hardware, epoxy resin, Arduino, motor, custom circuit board (printed with Laura Forlano’s data), led lights, electrical pipes and programmed with Laura Forlano’s insulin pump alert data, Variable dimensions. Original sound by Seth Cluett. © Itziar Barrio

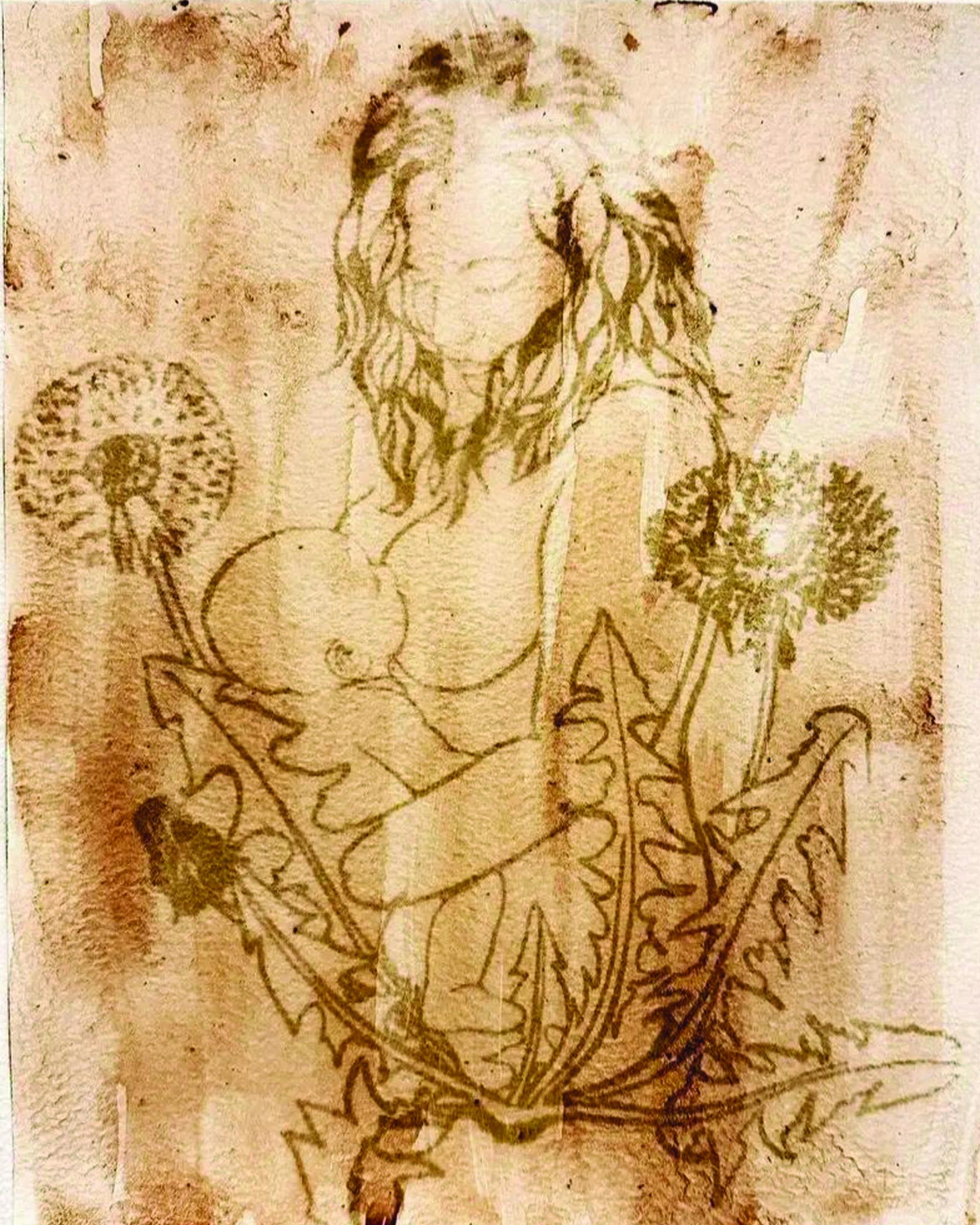

Cynthia O'Neill: Dandelion Rebellion

Inspired by the field of eco-crip theory, Dandelion Rebellion is the crip author’s art-as-research project focused on accessible nature, environmentalism, and activism for weedy species such as the dandelion. Drawing on relationships between dandelions and disabilities, Dandelion Rebellion investigates urban nature and examines multispecies relations and responsibility. Accessibility is central to this project’s design, participation, and conceptual process in digital and analog forms. Even as this project practices a model of accessibility as compliance, it also envisions a more fundamental reconceptualization of access called crip nature

natural cork tops, each filled with brown dandelion seeds. (© Cynthia O’Neill)

child in the embrace of a dandelion. (© Cynthia O’Neill)

stitchwork patterns in each leaf. The threads are a variety of colors. (© Cynthia O’Neill) (See the article in this issue by Cynthia O’Neill.)

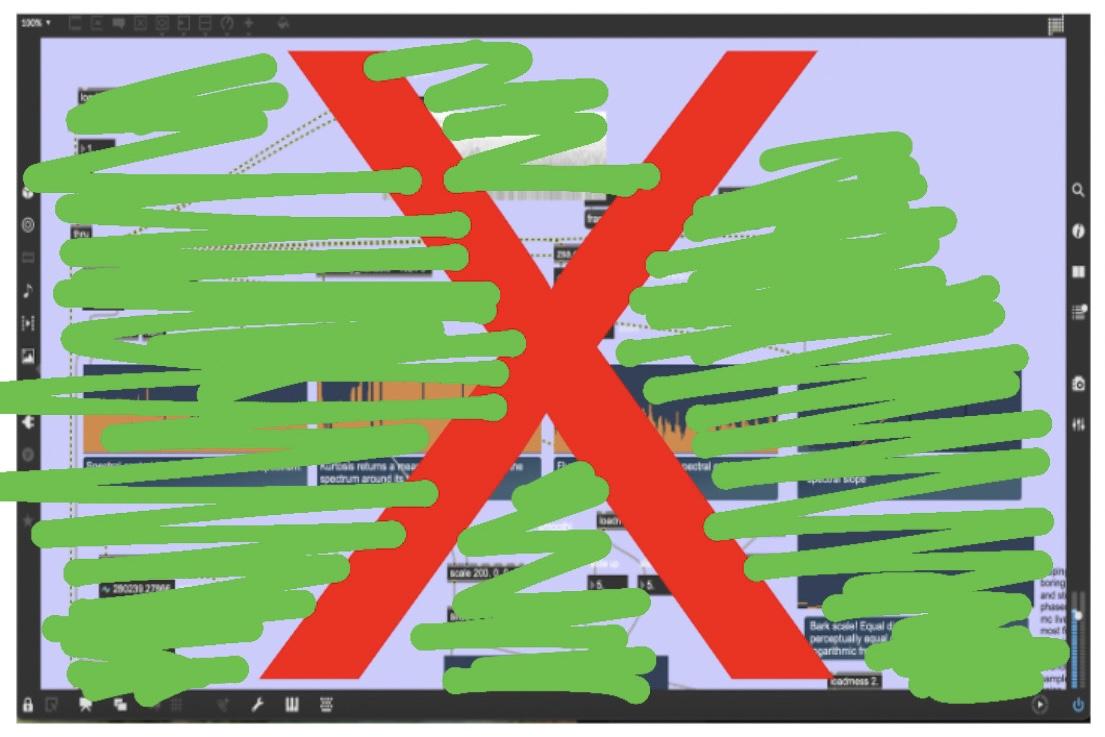

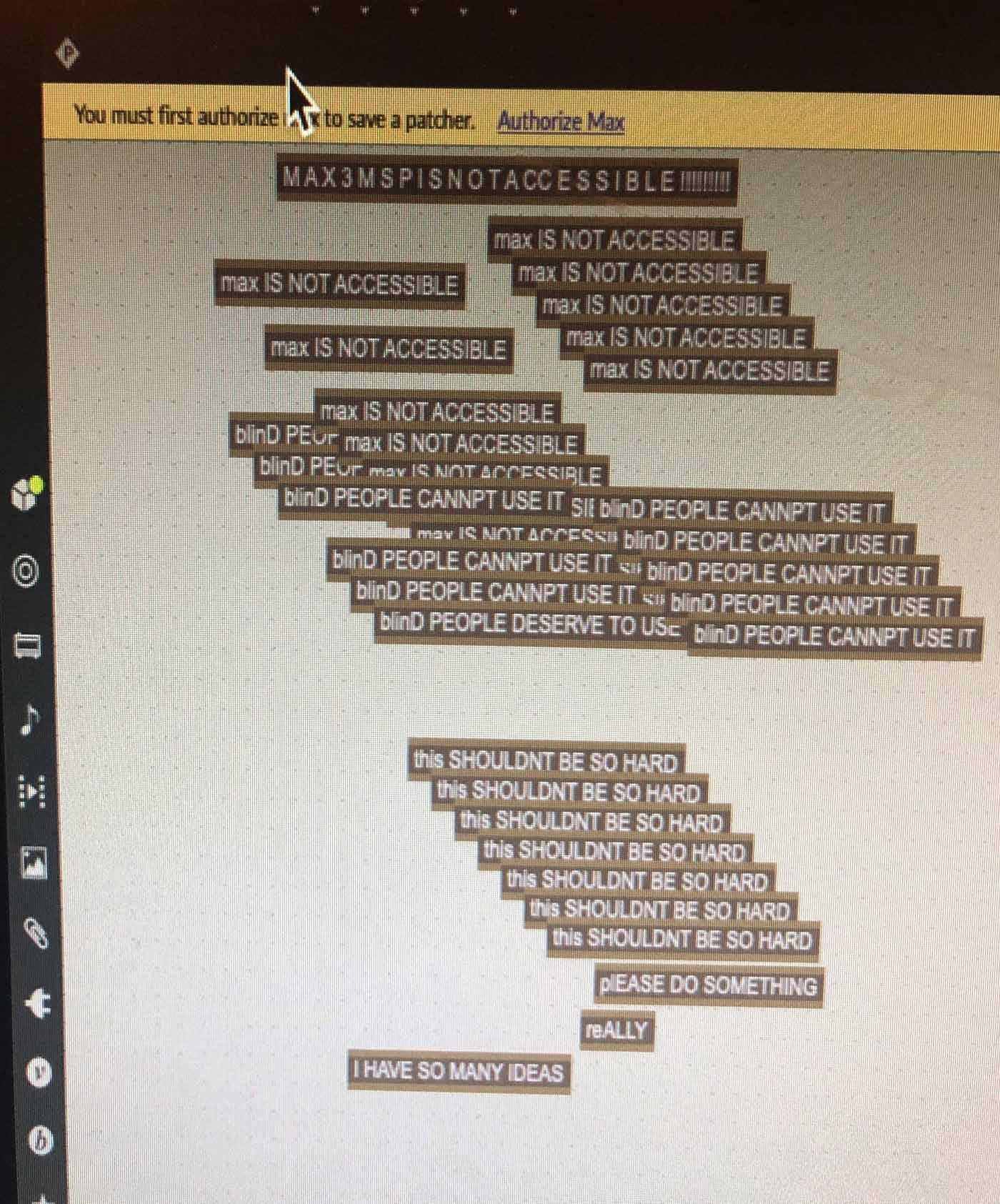

Meesh Fradkin: Plus, Noise Unlock

What happens when speech synthesis applications are incompatible with certain software? This essay considers how inaccessibility within the software and programming language Max is sonically, aesthetically, culturally, and ideologically amplified through a case study of “plus noise unlock,” which is the sound made by the author’s computer when she attempts to use a screen reader within a patcher window.

Olivia Ting: Between Piano and Forte

The author connects reviving her piano practice after a 20-year hiatus with her deaf right ear “learning” to hear again with a cochlear implant. She touches upon parallels between the physiology of the instrument and her own body, and how they inform the inquiry for her Leonardo CripTech Incubator/Thoughtworks residency project Song Without Words.

(© Olivia Ting. Photos: Will Tee Yang.)

Song without Words Audio Described

Indira Allegra and Allison Leigh Holt: How Can It Not Know What It Is?

How Can It Not Know What It Is? is a conversation that uses the revered sci-fi filmBlade Runner(1982) as a frame to explore the role of memory and affirming disabled identity in collective humanexperience, specifically concerning technology, the power of self-knowledge, and how theseconceptsintersect with capitalism and contemporary politics. In anopen conversationexcerptedhere, the artist-authors discuss what it means to be wholly human, navigating subjects from memory to extendedcognition, from national mythology to the ethicsof AI.

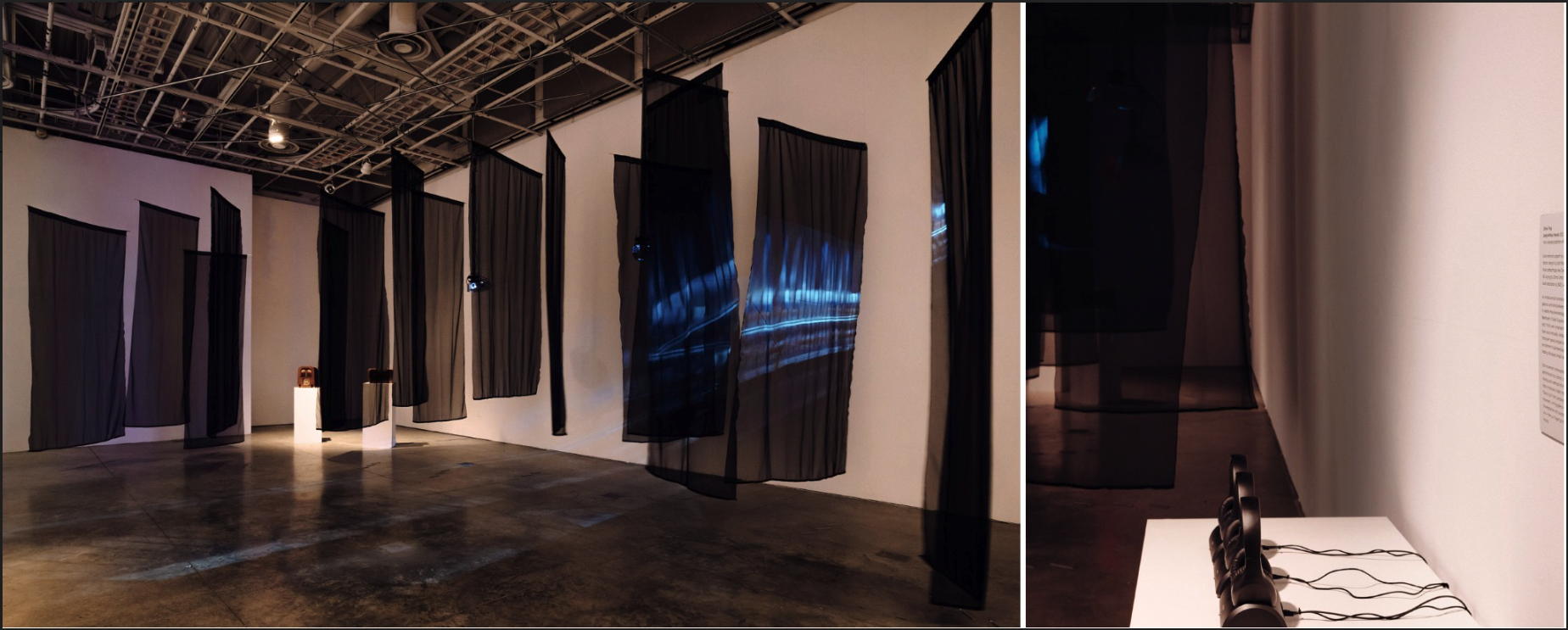

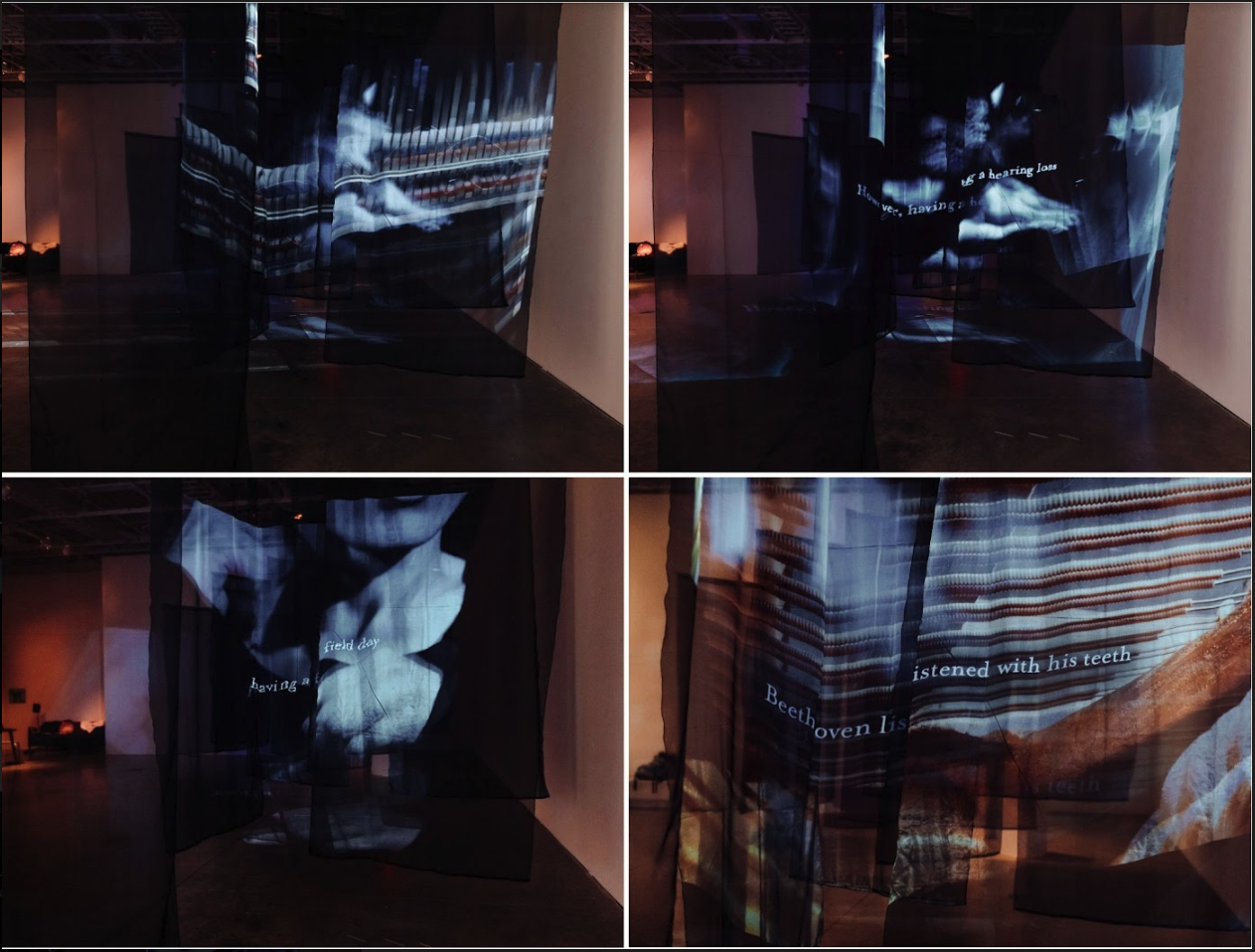

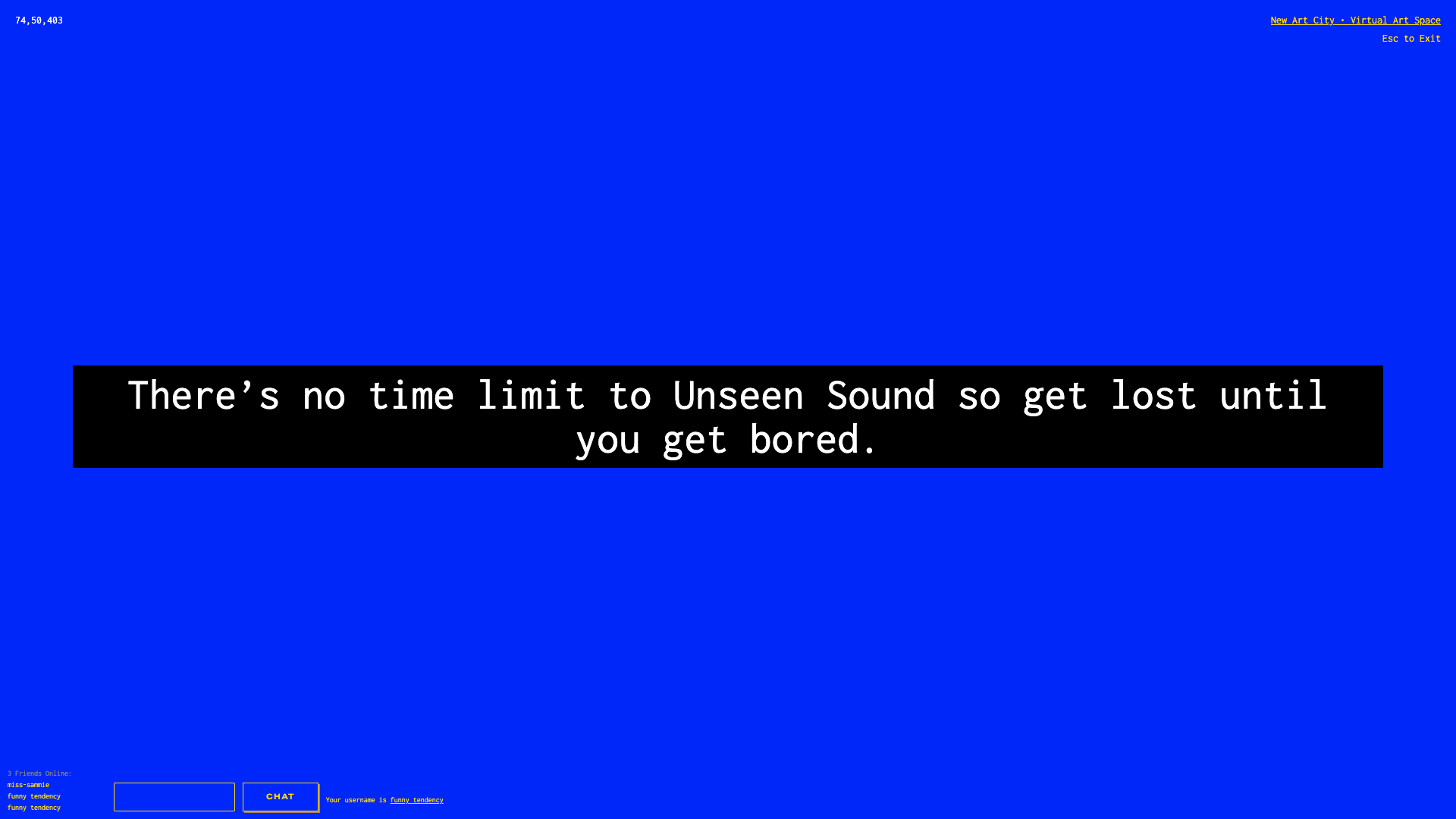

Andy Slater and Elizabeth McLain: Unseen Sound

Elizabeth McLain interviews CripTech incubator artist Andy Slater about Unseen Sound (2023), his work for E.A.A.T.: Experiments in Art, Access and Technology. Slater discusses accessibility as artistic practice, the exclusion of blind folks from augmented and extended reality, and experimental art’s capacity for fostering access intimacy. While developing Unseen Sound, Slater experienced failures in access and technology. Hyperactive listening—the key to Slater’s creative practice—enabled him to pivot and continue the fight for accessible extended reality (XR) technology. In the process, he makes the case for a brilliant blind future by making noise in public spaces and leaning into the weirdness.

homage to Derek Jarman’s 1993 film Blue

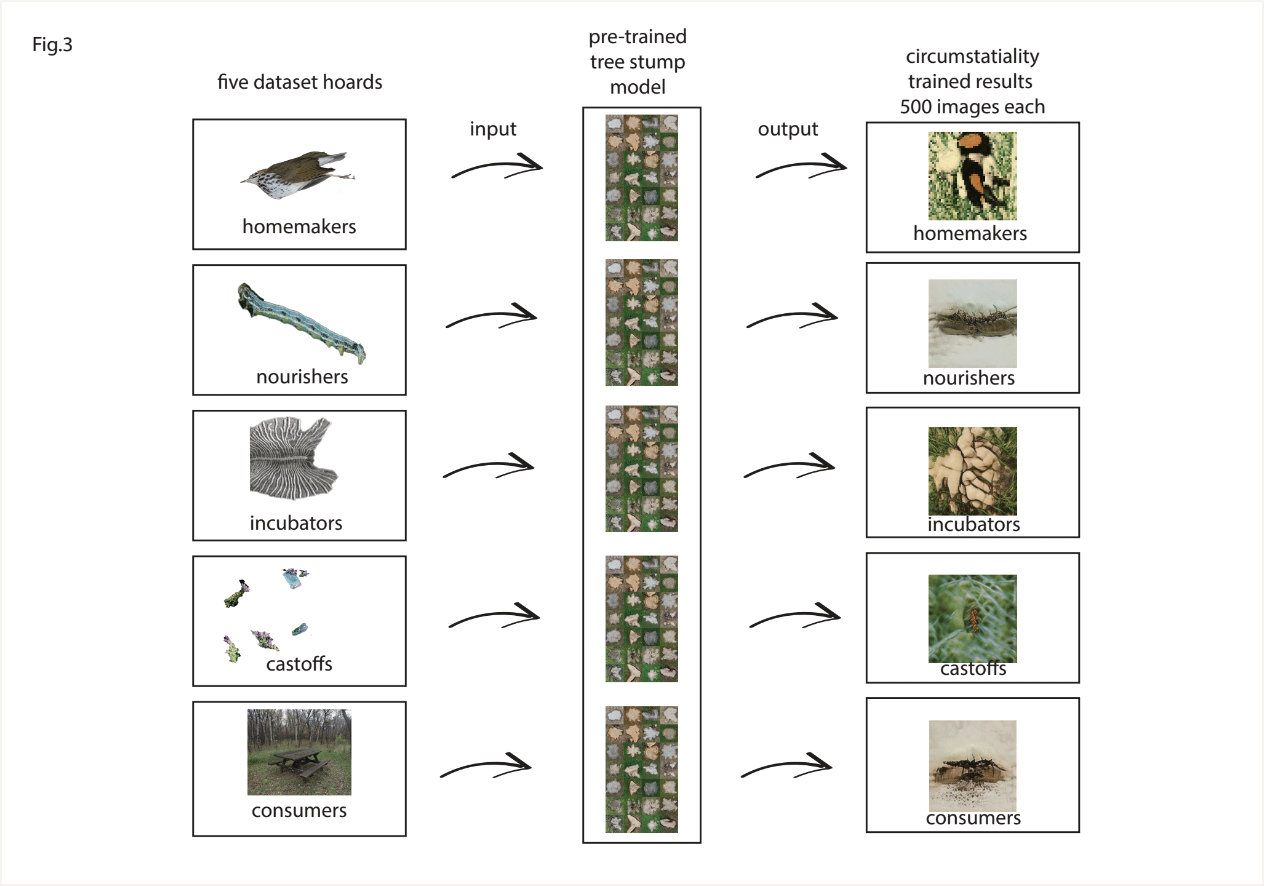

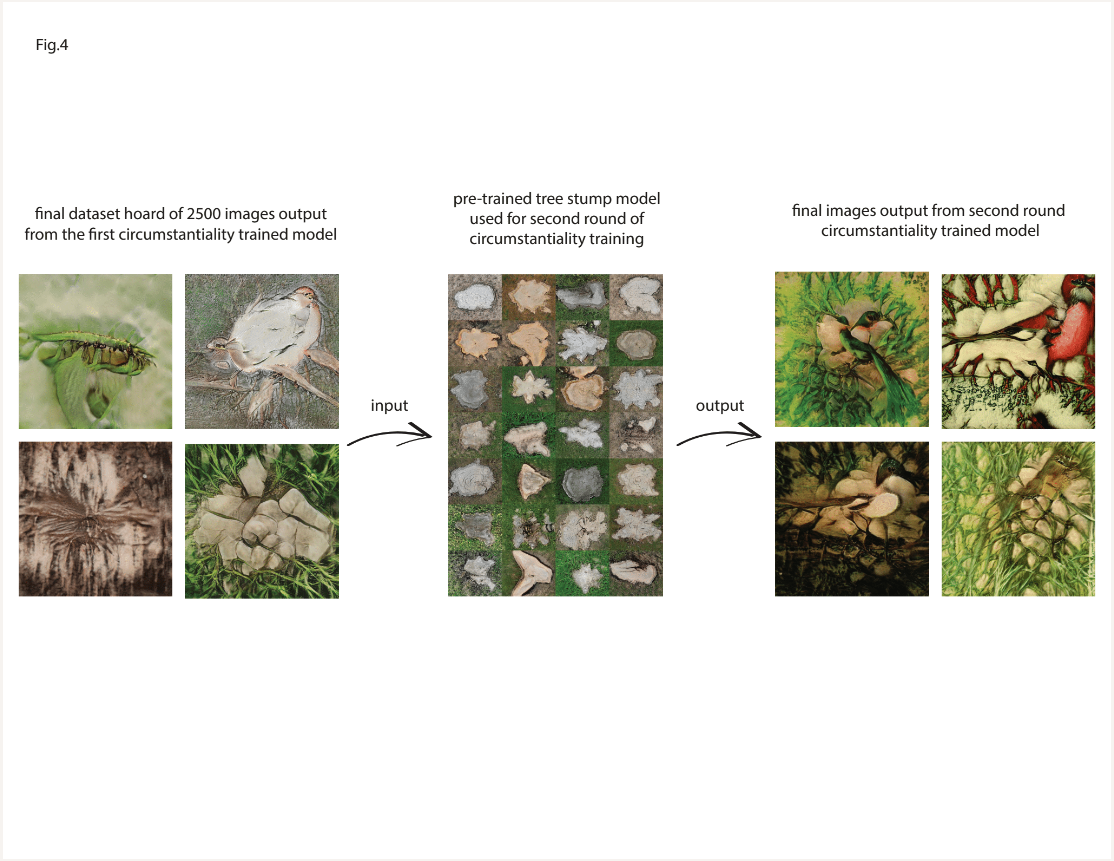

Erika Jean Lincoln: Crip-Techno-Tinkerism

The artist discusses the development of their crip-techno-tinkerism methodology and its application to machine learning. They outline how their tinkering with the creation of datasets and the manipulation of transfer learning within machine learning models can reflect the diversity of neurodivergent learning.

Ysolde Stienon and Marina Tsaplina: Primitive way country come look inside

A disabled poet with Rett syndrome and a disabled performing artist with type 1 diabetes document their 12-month artistic collaboration to illuminate ground-time: the nonverbal, expressive dynamics of embodied communication. Five “communication moments” between the artists (documented in writing, video, and photo) are described. Potentials and limitations of augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) technologies, specifically Tobii Dynavox eye-tracking technology and Communicator 5, are discussed. Additionally, the authors question the clinical diagnostic category of “intellectual disability” on the grounds of disability justice, decolonial science, and philosophy. Communication-assistive technology platform developers are challenged to consider relational embodiment as the foundation of communication in design decisions regarding platform function. Technologies should facilitate improvisation and nonlinear expression—verbal and nonverbal— while maintaining freedom of nondisclosure. The right to opacity in communication is also discussed.

This brief video is an introduction to Ysolde and Marina’s article and artistic collaboration. Ysolde’s machine-mediated voice was pre-recorded and laid over the video. The painting process documented here is a record of Ysolde’s bodymind rhythms. The brushstrokes foreground the way Ysolde’s bodymind speaks and communicates. The brushstrokes are part of Ysolde's voice.

This video documents a conversation between Ysolde and Marina where they were reflecting on Ysolde’s experience of being over-medicated. Disability performance artist Petra Kuppers invited Ysolde and Marina to contribute a movement or gesture to her project, the Crip/Mad Achive, that had to do with medical incarceration. Ysolde contributed a gesture of a feeling of freedom from over-medication. This video is unedited, and the non-verbal embodied communication between Ysolde and Marina - conceptualized as ground-time - is kept in full. The context for this video is described in greater detail in the article.

This video captures a communication moment of improvised response, where Ysolde is responding to the content in Video 2. This is a vivid example of how Ysolde will combine words and sentences that were programmed into her Communicator for a different purpose (i.e. Philosophy class) and apply them to new situations and contexts. Marina calls this communication moment a meta-DJ crip magic response mix. The context for this video is described in greater detail in the article.

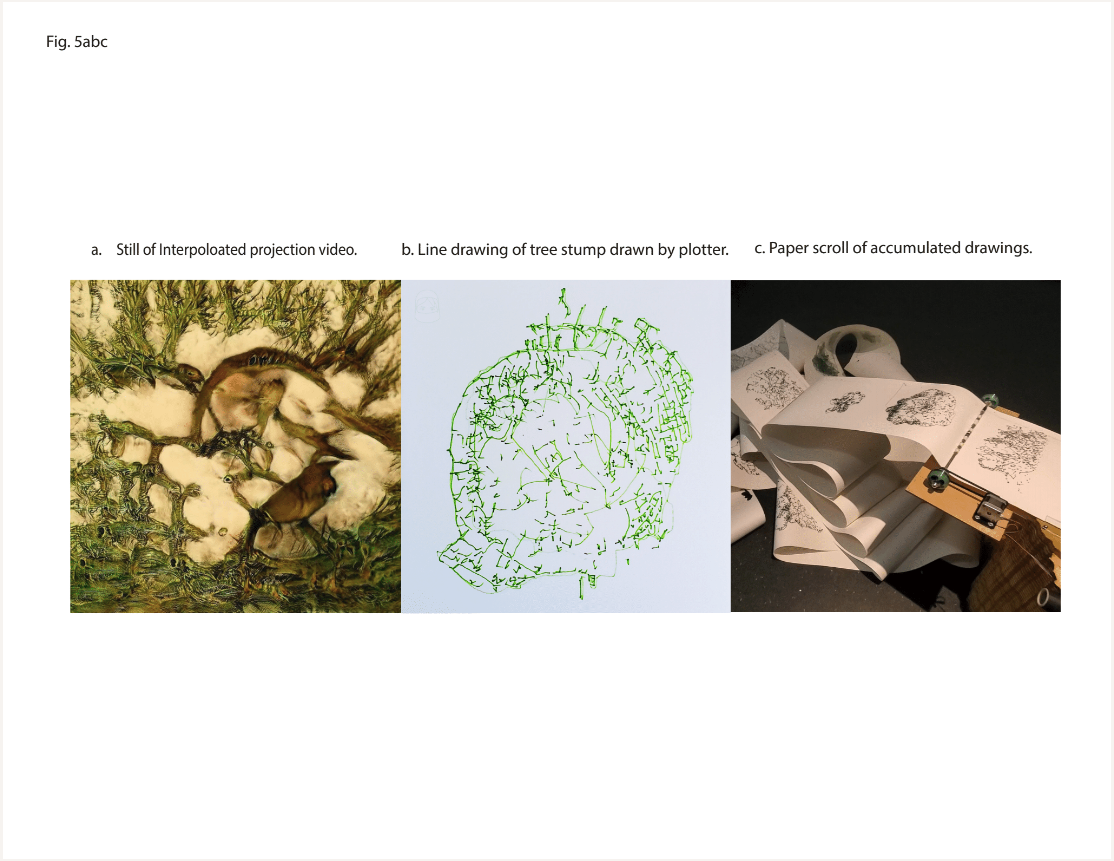

Aminder Virdee: Staring Back

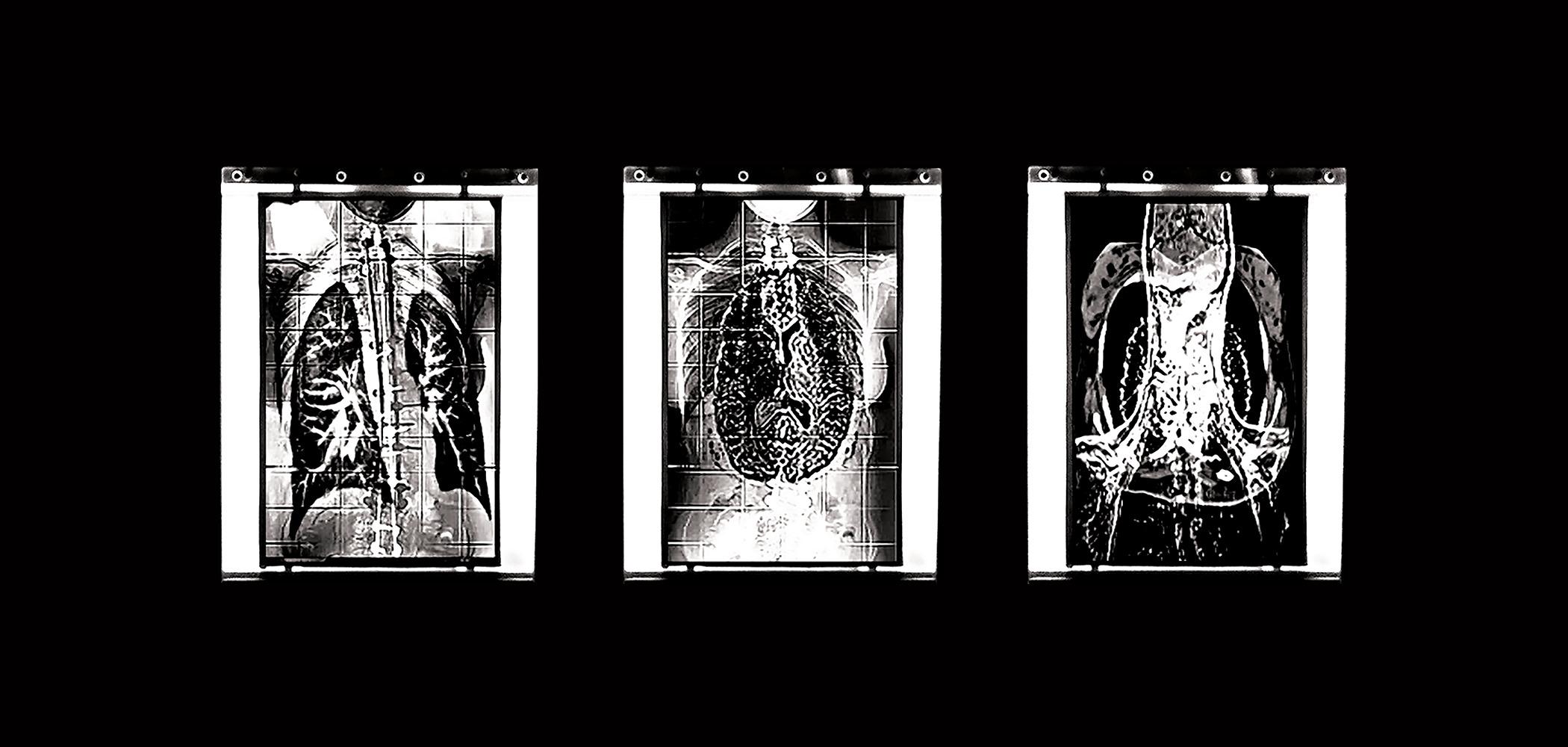

The author discusses their transmedia art installation, Eco-Crip: Cybotanical Futures (2021), as a site that critically explores and re-worlds the intersectional oppressions faced by disabled BIPOC individuals—centering on their own identity and complex lived experiences. Through a re-worlding lens, the artwork harnesses autoethnography, disability justice, and critical theory to confront and reclaim lifelong systemic oppression and medical surveillance, integrating computational art and digital painting to reconstruct medically quantified bioimaging and South Asian botanical archives into alternative “Cybotanical” futures. The author traces this work back to their earlier piece, Keep This Leaflet. You May Need to Read It Again (2014), a seminal creation in their criptech journey. Eco-Crip: Cybotanical Futures embraces a DIY ethos to hack and decolonize archives and technologies, navigating multifaceted meaning-making where beauty and pain converge—mapping new frontiers of crip technoscience art that challenges various systems of power and their associated gazes.

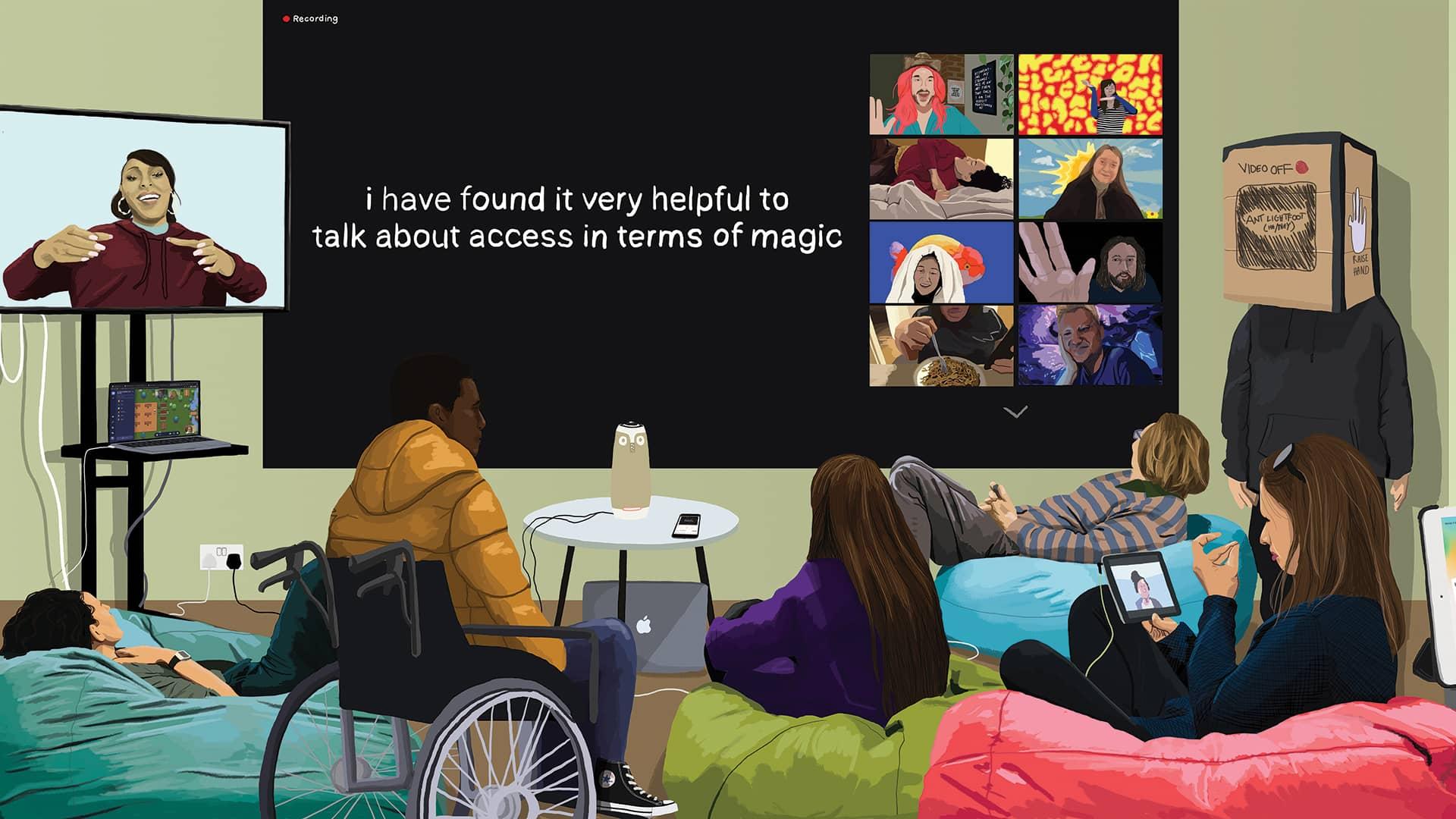

Aimi Hamraie and Kevin Gotkin: Remote Access

Since 2020, Kevin Gotkin has spearheaded disability nightlife events for the virtual Remote Access series for the Critical Design Lab, a multidisciplinary and multi-institution arts and design collaborative. Aimi Hamraie directs the Critical Design Lab and coined the term crip technoscience. Hamraie interviews Gotkin about the genesis of this disability arts and culture party and how it has evolved into an ongoing experiment in critical access-making. The authors focus on the elements of artistic production, presentation, and exhibition that required crip technoscience interventions before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

![White text on a black screen: “which means access is heartbreaking too”. Underneath, text of the same size in brackets: “[here it’s like i becomes something else]”.](/criptech/sites/default/files/styles/fullwidth/public/inline-images/Hamraie_Fig4.jpg?itok=ee9uWeUe)

Frank Mondelli and Jennifer Justice: Aesthetic In-Access

Metaverse technologies, such as spatial audio, virtual reality (VR), and augmented reality (AR), present new possibilities for disabled artists. To explore how artists use metaverse technologies—as well as the frictions that inhibit access—the authors describe the events of CripTech Metaverse Lab, which invited a cohort of disabled artists to a three-day workshop featuring metaverse experiences and a speculative design lab. Observing how participants creatively navigated these encounters, the authors introduce “aesthetic in-access” as a shared praxis developed by disabled users that transforms barriers to access into artistic expression. In doing so, the authors outline a metaverse future that centers disabled people’s expression and joy.

Darrin Martin: Experimental Modalities

In collaboration with Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), a nonprofit video arts distributor, the author has found videos in EAI’s collection that may reflect upon themes of disability and/or engage modes of access like captioning and audio description. The video/film works referenced in conceptual and performance practices have been broadly tethered to the word “experimental” and situated in this context to engage with accessibility even for works that resist and challenge the very nature of legibility. This essay is the author’s first attempt to explore an archive to identify video artworks that represent disability (whether deliberately or not) and present alternative modes of access (whether deliberately or not) with the intent of laying a groundwork for curations that tap into possibilities within accessibility formats.

color, silent. (© Phyllis Baldino and EAI)

(© Lawrence Andrews and EAI)

Shana Moulton, Whispering Pines 6, video still, 2006, 5:45 min, color, sound.(© Shana Moulton and EAI) (See the article in this issue by Darrin Martin.)

Megan Johnson, Eliza Chandler, and Carla Rice: Resisting Normality with Cultural Accessibility and Slow Technology

Although the COVID-19 virus continues to circulate, there is an increasing insistence that the world “return to normal.” In this paper the authors resist this pull to normalcy and the way it devalues the knowledges, vitality, and livelihoods of disabled people. They examine the crip technoscience practices used during the 2022 digital gathering Practicing the Social: Entanglements of Art and Social Justice, situating them as examples of cultural accessibility that engage with slow technology to provoke crip(ped) ways of being in time. They argue that sustained engagement with cultural accessibility offers a different path through the pandemic, one that centers access and resists the way necropolitics devalues disabled life.

Leonardo Gallery: Experiments in Art, Access and Technology