The Mindful Mona Lisa: River and Bridge, or, the Politics of Sustainability

What does the bridge in the Mona Lisa mean?

This simple question popped into my head on an airplane flight in mid-2019 and has interested me ever since.

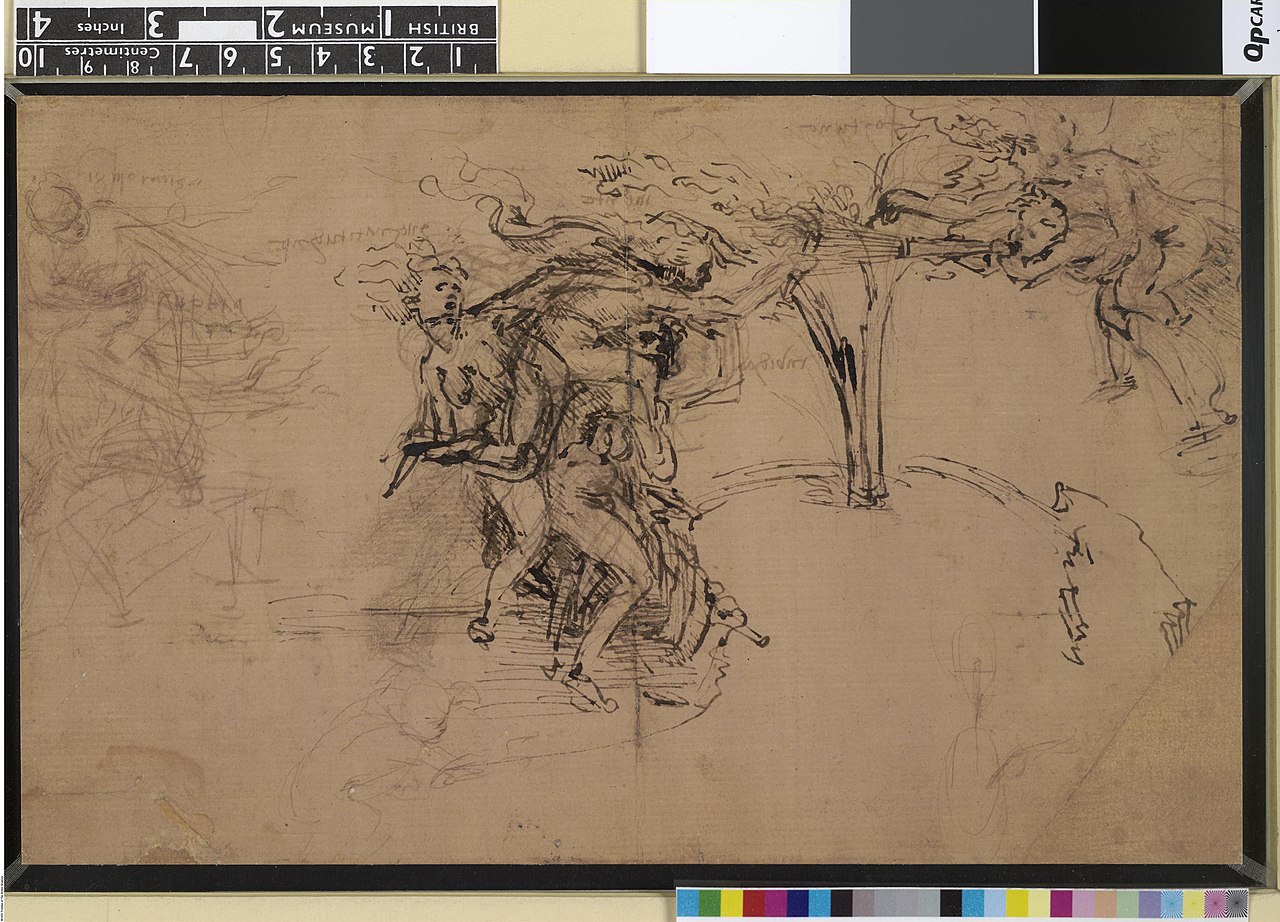

Most Leonardo scholarship addresses the bridge, if at all, only in asking whether it depicts a real bridge somewhere in Tuscany. A few scholars over the last decade (Zwijnenberg 2012/2020, Isaacson 2017, Geddes 2020) have mentioned the bridge as a “connector” of the background, representing nature or the primeval past, to the human or present realm of the sitter.

Yet the connection I sensed is that the bridge is also linked to the garment both visually and thematically. Both represent technology, engineering, and the “built environment” humans create and traverse as well as inhabit. This dual metaphor is further juxtaposed to the allegory of the sitter as Esperienza, a word meaning both “experience” and “experiment," who Leonardo personified as the “maestra” (teacher, guide) and “common mother of all the sciences and arts.”

As Leonardo wrote, “Painting is poetry which is seen and not heard, and poetry is a painting which is heard but not seen.” Hence the interconnections between Dante and Leonardo, which were so instrumental to integrating literature, visual art, and the sciences throughout the Italian Renaissance, demonstrate the deep roots and essential role of today's “environmental humanities.” Both Leonardo and Dante were concerned, ultimately, with sustainability: of social relations, political community, the ethical practice of art and science, and the relationship of humanity to the natural world.

Today sustainability in diverse forms is perhaps our most urgent challenge, linking it to the political realm with an intensity that will profoundly shape the 21st century.

In 2022 this blog will explore some political ideas and debates surrounding Leonardo’s contemporary and sometime colleague, Niccolo Machiavelli (especially his concept of “fortune” or history as a river), and their relevance for society’s attempts to achieve a positive, constructive, and resilient politics of sustainability.

Since Dante patterned multiple works on the ten celestial spheres, each of which represented a field of knowledge (the seven Liberal Arts, plus physics/metaphysics, ethics, and theology), each blog will feature one “sphere” as a metaphorical prompt or topic of comparison.

The first sphere is the moon, representing for Aristotle the study of grammar: it is something like knowledge’s starting point. (In Leonardo’s visual language, it might compare to drawing.) The moon also symbolizes contemplation and meditation in many traditions, which may serve as a basic starting point or grammar for the politics of sustainability: what is the role of meditation in brain health, and brain health in the prosocial behaviors undergirding sociality, dialogue, and reconciliation? How might mindfulness and contemplation relate to the concept of Esperienza, and technology, and the Mona Lisa?

In contrast to mindful contemplation, Machiavelli’s Il Principe (The Prince) seems to favor strategic action and relegates meditation at times to wishful or neglectful reverie. Just from the standpoint of stress-management alone his dictum “it is better to be feared than loved” would indicate a risk of chronic stress and may create barriers to sustainable wellbeing of both leaders and communities. Dante might have characterized this as “the haste that robs all actions of their dignity,” or as Leonardo wrote, “they who think little, err much.”

Contemplation in art and science may seem an obscure luxury in times such as ours, and may not seem to offer direct solutions to crises such as the horrifying recent collapse of European peace. Yet contemplation has always been a source of life and breath to both conscience and creativity, and the health of these may well determine how resilient our most cherished values will prove to be during a century of deep uncertainty, constant stress, and sometimes catastrophic change.

Next blog: sustainability and modern communication